Finance for non-finance directors: Part 1

A couple of years ago I got some excellent training on finance from a finance director at the FT. At the end of last year I went on a longer, more intensive course from the IoD, aimed at non-finance directors, and I learned LOADS.

In this post I will cover some important principles about company finance, sources of company funding and financial statements, and include a quiz!

In the follow-up post on Wednesday, I’ll give the answers and cover some accountancy principles and on Friday I’ll cover how to evaluate whether to invest in a company or a project.

The role of finance is to enable the organisation to meet its strategy

"Finance without strategy is just numbers;

Strategy without finance is just dreaming"

– Emmanuel Faber, CEO at Danone

The Finance Director’s role on a board is to provide financial and strategic guidance and make sure the right policies and processes are in place for sound financial management. Non-finance directors also have a duty of care, and need to be able to understand finance sufficiently in order to be able to challenge effectively, as well as think about the value of the work they do or sponsor.

Financial strategy is about the use and management of resources. It is driven by the corporate strategy.

While we learned a lot of practical information, most important were three key messages the course leader impressed upon us throughout the course: “so what?”, “it depends” and “profit is not cash”.

“So what?”

There is a difference between financial direction and accounting. The question we always need to be asking about financial facts and figures is “so what?”. What’s the story about the numbers, what are the numbers telling us? “Why are you telling me this?” “What are 3 key things I need to know about this?”

Accountants give data, finance directors give information. You are right to keep asking until you understand the message being conveyed by the figures.

Board members are jointly responsible for the financial health of the organisation, and even for those not yet at that level it’s useful to remember the importance of making sure you understand the details, even if you think it’s not your area of expertise.

Board members may not have to do all the work involved, but they remain responsible: “You can’t delegate the responsibility but you can delegate the task”.

The board should be challenging, asking questions. Our instructor said that as an outside advisor or potential investor, it is a concern when she finds a board where they all agree with each other. Even as a non-executive director it’s not good enough to say you didn’t understand.

“It depends”

It turns out that, like my disappointment when I found out that maths was not in fact a field of science in which it was possible to know everything, the same is true of finance. The figures given are not true facts. They are subjective estimates, based on what you think will happen next, and as a consumer of those figures you need to understand the assumptions being made.

For example, if someone buys something from you, you make an estimate about when they’ll pay you, and whether they will indeed pay you the full amount – you may need some provision for bad debts. I will talk more about this, but the main take-home message around this was: whatever the question about finance, the answer is very often “it depends”.

“Profit is not cash”

This was the main message that the director of the course wanted us to take away. Profit is not cash. Making a profit does not necessarily mean you are making money, and profit alone is not enough, you also need cash.

Profit is where you sell something for more than you estimate it costs. This is an example of an assumption as I mentioned above. You do not actually know exactly how much it cost. To give a simplistic example, you get a block of wood and reckon you can make four tables. You then base the sale price and estimate of profit on that. But actually, something is wrong with one part of the wood and you only managed to make three tables.

In fact, profit, rather than being something cut and dried as I had previously thought, is one of the things that includes the most estimates and assumptions.

In addition, profit is what you record in the profit and loss statement, not cash flow. Cash flow is NOT a determinant on whether you have earned the sale. It’s irrelevant whether someone pays or not – it’s recorded as revenue in the profit & loss statement. Even if they don’t pay, you still made the sale – all it means is you have a bad debt. This is better information as well, so you know at the end of the year approximately how many of your sales didn’t pay you.

In fact, when looking at the previous year, our instructor said 65% of the companies that had failed in the UK had increased their profit that year. The commonest cause of failure due to liquidity is growth – the company grows too quickly and can’t fund it.

Limited company vs partnership

We then talked about company structure.

“Limited” company means there is limited liability to the shareholders (the owners). In a partnership, liability is unlimited.

So why would you form a partnership? It used to be mandatory to allow for professional advice, and there used to be a tax advantage. Now the main benefit is that you do not have to make any information public or even register with Companies House (or pay the associated fees).

As an investor, it’s not a good idea to invest in a partnership unless you are going to be involved day-to-day because of the unlimited liability.

With a limited company, the company is a separate legal entity, so you can separate ownership and management. Management (i.e. the board) are the stewards to safeguard the assets on behalf of the shareholders. If you are both (e.g. on the board, and also a shareholder) be careful – you have two different sets of responsibilities and risks.

Private vs public

A private company is one that cannot offer its shares to the general public for trading. They have Ltd (or Limited) after their name.

A public company is one where shares can be marketed or traded. They are more likely to have external shareholders. A public company has Plc (or Public Limited Company) after their name.

Public doesn’t mean listed. A listed company is one where shares are officially listed and traded on a stock market, for example the London Stock Exchange.

There are about 4m registered limited companies in the UK; fewer than 4% of them are public, and about 800 are listed on the main market of the London Stock Exchange.

There are fewer listed companies than there used to be as there is more regulation now, meaning some companies de-listed rather than comply. For example insider trading wasn’t illegal in the UK until 1980, and since private companies can’t trade publicly, it’s easier not to fall foul of that law.

Listing a company allows it to raise capital much more easily. For example, Facebook listed to create an exit route for the original investors. It’s a way of making it clear what the value of the shares is, and making it much easier to sell them.

Company funding: debt or equity

There are two sources of equity: share capital – money you get from selling shares to investors, and retained profits – profits you made in previous years that you did not return to investors as dividends.

Note that retained profits – also called retained earnings and sometimes reserves, though reserves is not precisely the same – is not a sum of money; it’s not cash, it’s just the cumulative amount of profit from previous years that has not been paid out as a dividend.

With equity, you have no legal obligation to pay anything back to shareholders.

Debt is money you borrow, for example from the bank. With debt you do have a legal obligation to repay it, and also interest has to be paid. However, it can be a much easier and quicker way to raise money than a funding round from investors.

The legal obligation to repay makes debt a liability. Equity is not a liability.

The financing decision depends on various factors

What balance you choose between debt and equity depends on:

- the life‐stage of the business

- what the funding is for

- whether the company is private or public

- whether the funding is for long‐ or short‐term use

Considerations include:

- risk – there is more risk to the company in debt than in equity

- control – with equity, shareholders might take control

- flexibility – debt is more flexible, you can pay it back if you don’t need it, and it’s quicker to raise

- tax – interest can be a tax-deductible expense, whereas dividends are not

- possibility of raising more – if equity, shareholders should be open to investing more, and a successful rights issue can raise the value of the shares because it indicates strong belief in the future growth of the company

Financial gearing and leveraging

Financial gearing is a ratio of what proportion of your capital is equity and what is debt.

A company that has more debt than equity is said to be “highly geared”, or “highly leveraged”. It’s not necessarily a good or bad thing (“it depends”). For example, not borrowing is not a good decision if it means you miss opportunities. Your job as a director is to get the balance right.

Understanding financial statements

Financial statements are information so that the board and investors can make decisions. It is about the narrative as much as the statements themselves – the course leader said when you are learning about a company, don’t pick up the financial statements on the first day. If you’re there for a week, maybe spend one afternoon on them. The narrative is what is important.

The kind of information you are looking for from the narrative and financial statements are where does the finance come from? How does the company generate income? What are the costs? Which of those costs are discretionary/non-discretionary?

You should look at the three main financial statements: balance sheet, P&L and cash-flow.

The cash-flow statement from last year is probably the most meaningful. How quickly are they paying and getting paid, and what is their liquidity position? Are they a going concern? (I will talk more about liquidity and being a going concern in the next post).

The balance sheet is a snapshot of the business and its financial health

In the previous course I did on finance, we did not talk much about the balance sheet, so it was really interesting in this course to learn more about it.

The balance sheet is like an x-ray – a one-off snapshot – and your expectations of what good looks like vary, for example with the age of the patient. Similiarly with a balance sheet, is it a mature business or an early-stage start up? You’d expect to see different things on the balance sheet.

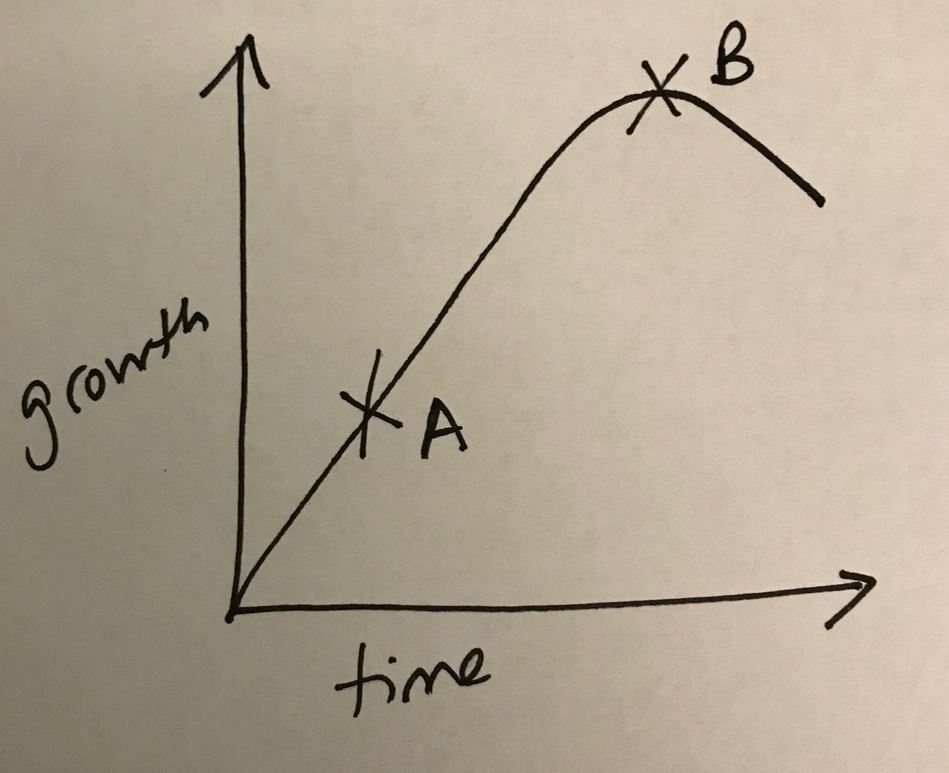

For example, this graph shows how you would expect growth to change depending on the age of the company. At A the company has higher debt. Growth requires funding. Plus it has had less time to build up from previous years. Growth can really increase from A.

At B, the company probably already has the market share and growth may well have peaked.

Balancing the balance sheet

On a balance sheet, roughly speaking, there are two sides. On one side you have the ‘uses’, i.e. what your money is being spent on, and on the other side you have the ‘sources’, i.e. where the money came from, which is split into equity and liabilities (debt).

Both sides of the balance sheet should add up to the same number (hence the name…). Neither debts nor shareholders’ cash is yours, but assets are.

The ‘uses’ side on the balance sheet is assets

Uses are ‘fixed assets’, or ‘current assets’.

Assets are things that are expected to generate value. For example, with a shop, you don’t expect to have to sell the property to recover the value; you expect to use the property as a place where people can buy from you and it generates value in this way.

‘Fixed assets’ are assets you generate value from over a period of time longer than the accounting period. They can be tangible, intangible or investments.

Examples of tangible assets are the building the company is headquartered in, the desks and chairs in the building, etc. Tangible confusingly can also be called PPE which doesn’t mean what we’ve come to understand in 2020, it means “Property, Plant and Equipment”.

Examples of intangible assets might include the website you work on and the related software, and examples of investments include things like investing in a supplier to ensure deliveries, or investing in a customer to ensure continuity of demand – strategic investments.

An interesting thing about intangible assets is that they only count if you bought them. So for example, M&S’s brand is not on their balance sheet because they built it up, they did not purchase it. There is currently a consultation about this kind of thing, as intangible assets are the vast part of the value of many companies (consider, for example, Facebook’s website, which they did not purchase and is therefore not valued as an asset).

This also makes it hard to reason financially about brand deterioration or reputational damage, unless it has a direct impact on sales.

‘Current assets’ are things where the value is generated from providing an immediate cash flow in the current account period, like receivables (i.e. money you are owed from debtors), cash, or stock (inventory).

The ‘sources’ side is liabilities and equity

‘Sources’ is split into equity (shareholders’ funds, retained profit), long-term liabilities (debt) and short-term liabilities (i.e. due within the next 12 months; this might include debt coming due, or things like electricity bills).

Valuation of all these things can be quite difficult

It is another thing that is not set in stone. For example, valuing stock involves being confident of the price you can sell it at, and you must value it at the lower of the cost or what you can get for it. So if you bought it for £1 per unit but are pretty sure you can only sell it at 80p per unit, the value is 80p per unit – but note that it’s still an estimate of what the value is.

Likewise when valuing receivables – it is not how much you are owed, but how much you can reasonably expect to actually receive; as some debtors will not pay, or will not pay the full amount owed.

The profit and loss statement (P&L) is about the profit and loss over a specific accounting period

I wrote about the P&L in my previous blog post about finance but without the context I have now.

While the balance sheet is a snapshot, the P&L covers the current accounting period.

But things don’t conveniently fall into accounting periods, e.g. you make a sale in 2020 but don’t get paid until 2021, or you pay staff to produce something in 2020 which won’t even be on sale until 2021. This is where accruals and matching come in. Accruals and matching dictate that sales and expenses are not recorded when the cash flow happens but in the accounting period in which they occur or to which they relate. I will talk more about this on Wednesday.

The P&L is all about timing, estimates and assumptions. Timing is everything. And this is why the P&L is also subjective. As well as the fact that the accounting period isn’t related to actual cash flow and accruals etc, there is also the fact that many expenses are not clearly directly related to a sale so are difficult to allocate correctly.

This is why profit is not cash.

Depreciation is an estimate

I wrote about amortisation and depreciation in my previous blog post. To reiterate: assets lose value over time, and this loss of value is representated as a cost on the P&L. Depreciation refers to tangible assets (e.g. office furniture, buildings) and amortisation refers to intangible assets (e.g. patents, trademarks, websites).

The value of the asset on the balance sheet is also reduced by the amount it’s been reduced by on the P&L, so it loses value over time. The current value of an asset on the balance sheet is called the ‘net book value’.

How depreciation is reflected on the P&L is a matter of what depreciation policy you adopt.

For example, it could be Straight Line depreciation – determine (or rather, guess) how long the asset will last and subtract an equal fraction each year. For example, if a laptop will probably last 4 years and costs £1,000, subtract £250 from the P&L every year for four years.

Another method is the Reducing Balance method, e.g. where you subtract a certain percentage of the remaining balance each year. (For the laptop, £250 in year 1. Then 25% of the remaining balance in year 2, so 25% of £750 – £187.50).

Note that there are several estimates being made here, as well as decisions about policy.

The order of the P&L matters

Start with: Sales/revenue

Deduct: cost of sales => this leaves gross profit

Deduct: operating expenses => this leaves operating profit/EBIT (EBIT = Earnings Before Interest and Tax)

Deduct: Interest => this leaves profit before tax (PBT)

Deduct: Corporation tax => this leaves profit after tax (PAT); also called net profit.

Note that if something is on a P&L it has an impact on profit, which can lead to poor decision making, as I mentioned before. For example, whether to build or buy software. Built software is an asset, on the balance sheet. Software you buy as a service is an operating expense, therefore reduces your profit. But building all the software you use is definitely not the right decision.

And a reminder: profit is an estimate. It will change, for example, if you change your estimate of depreciation. PROFIT IS NOT CASH.

Why we don’t like EBITDA

You may have heard the acronymn EBITDA. That doesn’t appear in the P&L above; EBITDA is Earnings before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation.

It’s a useful way of comparing companies’ relative operating efficiency, and means you don’t get bogged down in different depreciation policies. They are also subjective, so it’s nice to be able to ignore them. However, those companies will still have to pay depreciation and amortisation, and it is a big cost. (Warren Buffett does not like EBITDA and is credited with saying “Does management think the tooth fairy pays?”).

Private Equity companies like talking about EBITDA because depreciation and amortisation take place over time, and private equity companies don’t plan to be around for the long term; the company will be bought and sold within 5 years so who cares if they invest for the future or not?

As well as Warren Buffett, the IoD, and my instructor on the course are not fans of using EBITDA as a measure, because amortisation and depreciation are real costs.

A better measure is free cash flow, which I will talk about shortly.

The cash flow statement shows where funding has come from and how it is used

The third statement it’s important to understand is the cash flow statement. This was only introduced, for larger companies, in 1991.

There is nothing on the cash flow that cannot be calculated from the balance sheet, the P&L and the notes to the accounts, but it’s extremely valuable for understanding where the cash is coming from and going to, and what the actual position of the company is. The cash flow statement illustrates how funding has been generated and how it is used in the organisation.

The most important factor for an investor when deciding whether to invest in a company is management credibility. What are you going to do next to improve the company and make money for your investors? And one way to assess management credibility is looking at the cash flow. Does the cash flow match up to your strategy?

Free cash flow is how much cash there is for discretionary spending

That is how much cash there is, less operating expenses. That is, operating cash flow, adjusted to reflect:

- interest paid

- tax paid

- capital expenditure

- loan repayment arrangements

Free cash flow shows the true cash generation of the business, and allows you to assess:

- the impact of future capital projects

- repayment capacity for new loans

- whether dividends should be distributed

As a director, you need to know what your free cash flow is so that you can make strategic decisions.

Our course instructor said:

Profits: sanity

Cash: reality

Balance sheet analysis quiz

At this point in the course, we did a very fun exercise where we were shown the balance sheets of 6 companies, with a few notes about them, and had to work out which was which, thinking about what their business model was, what would be dominant on their balance sheet, and what proportion of other things would be on the balance sheet.

There is no way before this course I would have had the first clue of where to start, but our group got this all correct. Hopefully I have given you enough information above to have a go at this yourself, so here is the exercise. I’ll be back on Wednesday with the answers, and part 2 of my write-up.

- Barclays Bank

- easyJet

- The IoD (Institute of Directors)

- Morrison’s supermarket

- Apple

Notes

- The IoD does not own its buildings but has leasehold interests. Delegates attending courses pay upfront for courses to be attended over time.

- Like other banks, Barclays shows derivatives on both the assets and liabilities sides of its balance sheet.

- Facebook completed the acquisition of WhatsApp for $22bn in 2014. WhatsApp was founded in 2006, had annual revenues of $30m and was loss-making. Facebook continues to be acquisitive. Goodwill is only very marginally amortised. It continues to be a highly profitable business and has yet to pay a dividend.

- Apple started paying regular dividends in 2012 and has instigated a very active share buyback programme to return cash to shareholders. Borrowings were raised for this to take advantage of very low interest charges and to minimise their tax obligations. A high percentage of its profits are held outside of the US.

- All the balance sheets are in percentages, not absolute size so you can’t tell which is which from that.

- An empty cell indicates they do not have that kind of thing (or it’s so tiny as to be negligible)

| Uses: Assets % | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangible/fixed assets | 11 | 74 | 0.2 | 26 | 63 | 25 |

| Intangible assets | 4 | 0.7 | 4 | 7 | 20 | |

| Investments (long-term) | 31 | 8 | 28.1 | |||

| Inventory/stock | 1 | 7 | ||||

| Receivables/debtors | 7 | 3 | 29 | 19 | 4 | 8 |

| Cash & short-term investments | 30 | 3 | 22 | 51 | 19 | 42 |

| Other | 20 | 1 | 20 | 7 | 5 | |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Sources: Liabilities & equity % | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Payables/creditors <1yr | 31 | 33 | 46 | 61 | 32 | 7 |

| Payables/creditors >1yr | 42 | 20 | 29 | 10 | 31 | 6 |

| Other | 19 | |||||

| Equity/shareholders' funds | 27 | 47 | 6 | 29 | 37 | 87 |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Answers on Wednesday

The answers to the quiz and more on accountancy principles, project appraisal techniques and other interesting financial concepts to follow!

This is post one of three posts. You can read part two here and part three here.

If you’d like to be notified when I publish a new post, and possibly receive occasional announcements, sign up to my mailing list: