Finance for non-accountants

This is the first role I’ve had managing a large budget and I recently had some excellent training from my finance director colleague Isabelle Campbell. Here are my notes.

The role of the finance team in an organisation

Isabelle started by answering the question “what is even the point of a finance team?”

There is a lot to know about finance. The current regulations are on dictionary-thin paper and stack up about four feet high. So the finance team takes care of keeping on top of regulations, tax and the latest accounting standards, as well as reporting.

They do budgeting and forecasting, and can also advise on strategic decisions.

Accounting years are important

The first non-obvious thing I learned was that the concept of an accounting year is very important. This is because a profit & loss statement (P&L) is only for the current accounting year. So whether something is capital or operating expenditure (more on that in a moment) is defined by the value within or beyond the accounting year.

Most UK companies use the calendar year (i.e. January 1st to December 31st). Many instead follow the tax year (so April 6th to April 5th; or April 1st to March 31st). In the UK you can set your accounting year however you like.

Annual accounts

Every accounting year, most UK companies have a requirement to produce annual accounts. This can include a profit and loss statement (a P&L), a balance sheet and a cash flow statement of varying levels of detail and complexity.

We spent more time learning about the P&L rather than the other two, so I’ll talk more about that, but in brief:

- the balance sheet is a statement of the company’s assets and liabilities

- the cash flow statement is a statement that shows how changes in the balance sheets and P&L affect the cash. The cash flow statement is essentially a check on the balance sheet and P&L.

How to read a P&L

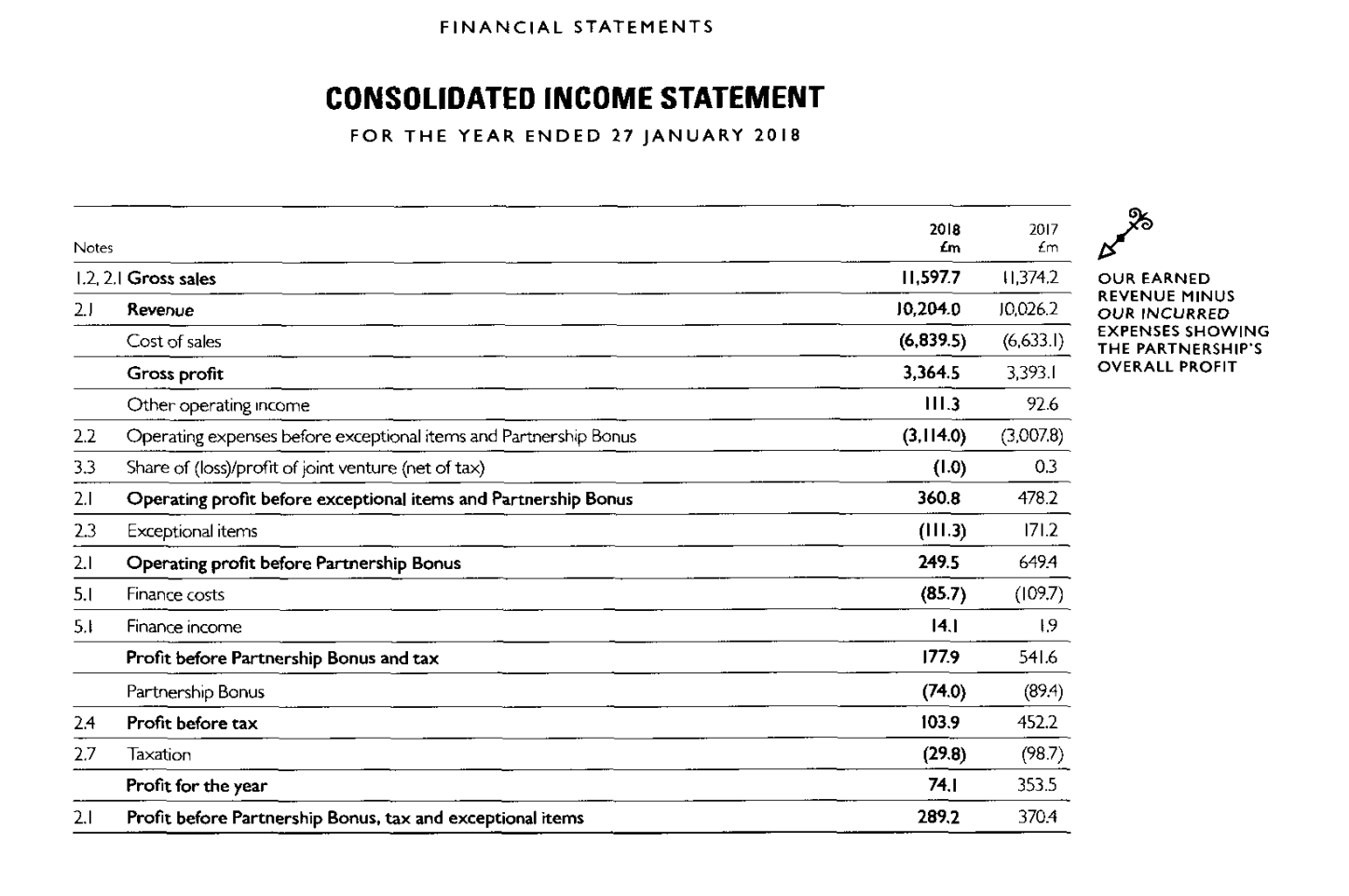

For example, here is John Lewis’s P&L for last year. It was an image in a PDF, so I’ve typed out the contents below.

| Notes |

2018 £m |

2017 £m |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2 2.1 | Gross sales | 11,597.7 | 11,374.2 |

| 2.1 | Revenue | 10,204.0 | 10,026.2 |

| Cost of sales | (6839.5) | (6633.1) | |

| Gross profits | 3,364.5 | 3,393.1 | |

| Other operating income | 111.3 | 92.6 | |

| 2.2 | Operating expenses before exceptional items and Partnership Bonus | (3,114.0) | (3,007.8) |

| 3.3 | Share of (loss)/profit of joint venture (net of tax) | (1.0) | 0.3 |

| 2.1 | Operating profit before exceptional items and Partnership Bonus | 360.8 | 478.2 |

| 2.3 | Exceptional items | (111.3) | 171.2 |

| 2.1 | Operating profit before Partnership Bonus | 249.5 | 649.4 |

| 5.1 | Finance costs | (85.7) | (109.7) |

| 5.1 | Finance income | 141.1 | 1.9 |

| Profit before Partnership Bonus and tax | 177.9 | 541.6 | |

| Partnership Bonus | (74.0) | (89.6) | |

| 2.4 | Profit before tax | 103.9 | 452.2 |

| 2.7 | Taxation | (29.8) | (98.7) |

| Profit for the year | 74.1 | 353.5 | |

| 2.1 | Profit before Partnership Bonus, tax and exceptional items | 289.2 | 370.4 |

There will be a scale. At the top, we can see the scale is millions (“£m”).

If a sum is in brackets, it’s negative. For example, “Cost of sales” in 2018 was “(6839.5)”, that means it was -£6,839,500,000, i.e. it cost them ~$7bn to buy or produce what they sold. (This may not include all costs – to see what all the parts are, we’d have to refer to note 2.1.)

The bottom line (hence the phrase!) is the revenue minus expenditure, i.e. the profit.

In this example the bottom line is £289.2m, though taxes, bonuses and exceptional items will come out of that. Somtimes the bottom line may be used to just indicate gross profit, i.e. before any deductions at all.

Capex and opex

Capex is capital expenditure. This means money spent on something that will have a longer term value; specifically this means a value outside of this accounting year. Buying a car for £30,000 would probably be capex, because you expect that car to last longer than a year.

Capex is money you spend on buying assets.

Opex is operational expenditure. This is money you spend on things that do not retain value for the company. For example, if you lease that car for £8,000 per year, that’s opex. There’s no value to the company. When you stop paying, you no longer have the car. Examples of opex include paying salaries and rent, buying stationery, etc.

Opex is the cost of operating the business in the year.

Capex and opex in the 21st century

All reasonably straightforward when talking about buying vs leasing cars. With some things it is obvious whether something is capex (for example, buying a fleet of cars) or opex (renting a garage).

But there are a lot of grey areas. For example, what if our car had actually cost £8,000 to buy? Should we capitalise that if we expect it to last more than a year, or should we in fact just consider it part of this year’s operating expenses? There are guidelines, but this kind of thing is a judgment call and something the finance department can help with.

It becomes even more complicated when you get into the kinds of work most companies do now.

For example, staff costs such as salary are generally opex. But if they are working on something capitalisable, like software, then there is a question there. Say you have a team of people working on building an A/B testing framework that you expect will be used for the next 5-10 years. That A/B testing framework is an asset that you could potentially capitalise, in which case you may be able to capitalise some or all of the staff costs.

Capex is not included in the P&L

Capex and opex are treated in different ways. One extremely influential distinction is that capex does not appear on the P&L. Instead, it appears on the balance sheet as an asset.

Technology is usually a cost centre

A cost centre is a part of the business to which you allocate costs and is not responsible for revenues. This is in contrast to a profit centre, which can add to the company’s costs and profits.

In most businesses, technology is a cost centre, meaning that the main way the technology department can increase the overall profitability is by cutting costs, and/or making the revenue-generating areas of the business more economical or efficient.

Cost centres generally do not produce their own balance sheet.

This can lead to misalignment of incentives

Focusing on a P&L rather than having full visibility of what sits on the company’s balance sheet can potentially lead to incentives that are not aligned.

A big example in software is buy vs build. In general, you should build things that represent your core competency and things that will give you a competitive edge, and you should buy everything else. So if you’re not a hosting provider, use cloud computing for your infrastructure and hosting.

However, that cost is not capitalisable. The company does not gain any asset from paying AWS or Heroku. This means the costs will appear on your P&L. If, instead of using cloud computing, you bought your own hardware and hired a team of people working full-time in a data centre you own, that would be very capitalisable and the costs would not appear on your P&L.

It’s clearly a bad idea, for a number of other reasons, but the incentives here can be poorly aligned.

Amortisation, depreciation and write-downs

Capitalised assets appear on the balance sheet. However, normally they lose value over time. This is called depreciation, and the annual cost of this is deducted from the balance sheet and charged to the P&L.

In the UK, ‘depreciation’ refers to the loss of value on tangible assets. There is also ‘amortisation’, which in the UK usually refers to loss of value of intangible assets, like brand. (US companies usually call depreciation amortisation, which can be confusing).

Sometimes assets lose more value than has been allowed for in a pre-determined depreciation or amortisation rate. In this case, the company might “write down” the cost, which means further reducing the value on the balance sheet. The amount it is reduced by is charged to the P&L. Whether to do this is usually a judgment call, though a company may receive pressure from their auditors.

Impairment and goodwill

A recent big example of a write-down was at the end of last year, when Verizon took an impairment charge of $4.6bn on their purchase of Oath (the company formed from Yahoo & AOL).

When a company buys another company, they have an expectation of the value that the asset will generate, as with any asset. If the purchased company turns out not to be delivering the value, for example due to changes in the market, government regulations, loss of brand reputation etc, then the asset is no longer worth what it was, and the owning company’s balance sheet suffers.

Part of the purchase amount agreed is the value of the assets. The remainder of the cost of the company is what is called “goodwill”: this is the difference between the assets that you can put a value to and how much you are willing to pay for it.

In the case of Verizon and Oath, the $4.6bn was a “non-cash goodwill impairment charge”, meaning the “goodwill” aspect of the deal was no longer considered to be worth what Verizon had paid, so they were taking a “write-down”, i.e. reducing the overall value of Verizon’s assets by $4.6bn, a figure which would have come out of Verizon’s 2018 P&L.

Budgets and forecasts

The P&L budget for the year is worked out towards the end of the previous year. It covers everything that might happen in the business in the next year. How many employees the company is likely to have, how much revenue from existing and new customers can be expected, etc. It also involves asking the question of what can be capitalised.

A forecast can be done at any point during that year, and takes into account new information. For example, you might do a Q1 (Quarter 1, i.e. the first three months of your accounting year) forecast at the end of March. Knowing what we know now about what’s happened in the first three months of the year, what do we know about the rest of the year? Forecasts might be a few months, or a few years.

A forecast may not always change the budget; so a Q1 forecast that shows a higher or lower than predicted revenue may not result in a revised budget, but it does mean at least that you are armed with the information.

How to find a P&L to read

If you want to browse the accounts of companies, you can! https://www.gov.uk/get-information-about-a-company will take you to the Companies House search (currently in Beta). I searched for John Lewis Partnership, and then ‘Filing history’. The image above is from page 85 of their company accounts. Quite a useful tip if you want information on a company you are thinking of joining, or even if you’d like to know more about the company you work at.

Smaller companies only have to file restricted information in their accounts, but there is still interesting information about them on Companies House, e.g. who the directors are.

This has only scratched the surface

There were loads of other things that we didn’t cover, and given that the regulations are four feet high, may not ever cover, but it was a really useful session and has given me much a better grasp of some of the competing priorities we need to think about.

If you’d like to be notified when I publish a new post, and possibly receive occasional announcements, sign up to my mailing list: