Replacing the SPA CMS

As part of my ongoing mission to update the SPA conference website, I had long wanted to replace the CMS. When I realised it was blocking the move to HTTPS, I knew the time was now. This post is about how I did that and what I learned.

The conference website used a CMS to generate the static pages

The functionality of the conference cycle, for example programme submission, reviews etc, is done through PHP scripts, but the generation of the static pages used CMSMadeSimple.

The CMS didn’t edit the site directly, it edited a staging site, which was in fact a subdirectory: spaconference.org/staging/. When the chairs were happy with the content in staging, they published it to the live site (another subdirectory, e.g. spaconference.org/spa2018) using a script called publish.php.

It wasn’t very secure

The staging subdomain and and the publish script were behind Basic Auth, which when coupled with the fact that the site was still HTTP (more on that another day) meant it wasn’t very secure. When new chairs joined the committee, I had to create their passwords for Basic Auth as I was the only one with access to .htpasswd, and email the passwords to them; very insecure. In addition, the publish script had the previous web admin’s credentials in it to allow it to work, which was a bit of a blocker to my plan of eventually open sourcing this code.

However, this is not a very high-profile website so the risk and impact of someone unauthorised gaining access is quite low. The CMS, while a bit dated, was relatively intuitive and easy for new chairs to use, so replacing it was not a high priority.

It was blocking the move to HTTPS

It became a priority to remove it when I discovered it was blocking moving the site to HTTPS. The issue wasn’t the CMS itself, but the publish script, which literally copied the page from the staging subdirectory to the current year subdirectory using curl. The version of OpenSSL running on the shared hosting didn’t support copying the page contents over HTTPS.

Because it’s shared hosting, it’s not possible for me to upgrade OpenSSL, so after considering various other ways to copy the site from staging to live, it became clear that the right solution was to bring forward my plan to remove the CMS and publish the site a different way.

Most of the pages were static so could be replaced with a Jekyll project

It was quite easy to choose Jekyll. I’m familiar with it from using it on this blog, and I know others are too. Hosting the project on GitHub meant that I could offload the issues around authorisation to GitHub, dealing with the security issues I mentioned above.

Using GitHub also has the advantage that people can see when others are editing and what changes are being published, and comment if neccessary. With the CMS, there was no way to tell if another user was editing at the same time. The publish script published everything, and a couple of the conference chairs had mentioned to me that this was a bit stressful, because there was no way of knowing if you were about to publish something half-finished that another chair was working on. With GitHub, you can see what commits have been made and what pull requests are open.

I also removed the necessity to run a separate publish script by setting the project up so that it deploys automatically to the live site on merge to master. This turned out to be quite tricky on shared hosting, so I wrote up how to do it.

The programme generation was a different kettle of fish

While most of the site content is completely straightforward, the programme generation was managed in a completely different way, not using the CMS. The programme was created via the PHP scripts, using a plug-in called Xinha as a WYSIWYG editor. Because the site is on shared hosting, this was vendored into our code, and was an old version.

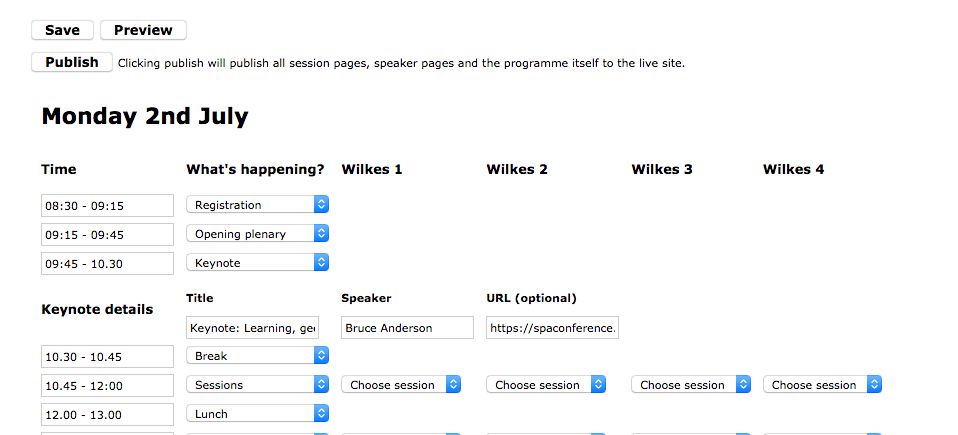

The accepted sessions were available to be added via a drop-down menu. When chairs published the programme, the accepted session links were expanded to include all the details about the session and the session leaders, with links to the supplementary pages.

The session and session leader pages themselves had to be generated separately, using a publishallsessions.php script.

The process was not intuitive, but in theory it worked quite nicely because you could just add the sessions you wanted via a drop-down, and publishing it took care of generating all the rest of what was needed.

However, when I looked into it, it turned out that the last programme chairs who actually used it were me and Andrew in 2014. Subsequent chairs had generated or hand-written the HTML in a different way, including manually adding all the session details.

I wanted to create a process that had the good features of the old process (like automatically creating the session and session leader pages) but was easy enough to use that subsequent chairs would actually use it.

The programme had to look like the rest of the site

The way it had worked previously was that the “publish” button saved the HTML for the programme (so not the whole page, i.e. not the header and footer) to the file system on the server. If you look closely at the diagram above you can see the ‘Publish’ button says “to staging only”.

The CMS then picked up the HTML from the file system, added the same header and footer as the rest of the site and published it along with everything else when the publish script was run. (This did mean that the preview and published programme HTML was actually available on the file system if you knew where to look, not even behind Basic Auth.)

Before launching the new Jekyll site, I did a proof of concept to make sure it would be possible to publish directly, rather than via the CMS.

I also looked around to see how other conferences generated their programmes, but I couldn’t find a good tool.

Working out how to generate the programme took AGES

It took a very long time to turn the proof of concept into a working process for generating the programme because there was a lot to unpick. The main challenge was making it look like the rest of the site.

I didn’t want to add it to the Jekyll project, because that is public and I think it’s important that the programme generation is done privately. You wouldn’t want session proposers to find out their session had been rejected by being able to observe you editing the draft programme. You might also not want it to be public who had pulled out of the conference or other changes you might make in the run up to publishing it.

I considered a number of options for how to do it, and concluded that adding it directly to the correct place on the filesystem on publish was the least worst option.

How programme generation works now

Instead of generating HTML and saving that to the file system, my changes saved the programme into the database. I created a very basic form for editing.

I had big plans for making it much prettier, but meanwhile the conference cycle marches on and I had to get something out before the programme meeting in March of this year, so MVP it is.

To keep it in synch with the Jekyll site, I added programme includes. These are included in the programme page so that when the rest of the site is generated they will change too – so, for example, if another item is added to the menu this will show up the same on the programme page.

<?php include('{$GLOBALS['pathToCurrentYear']}/programme_includes/header.html'); ?>

This means that when I’m retiring the site to go in the list of previous conferences, I’ll need to make sure to replace that with the actual HMTL.

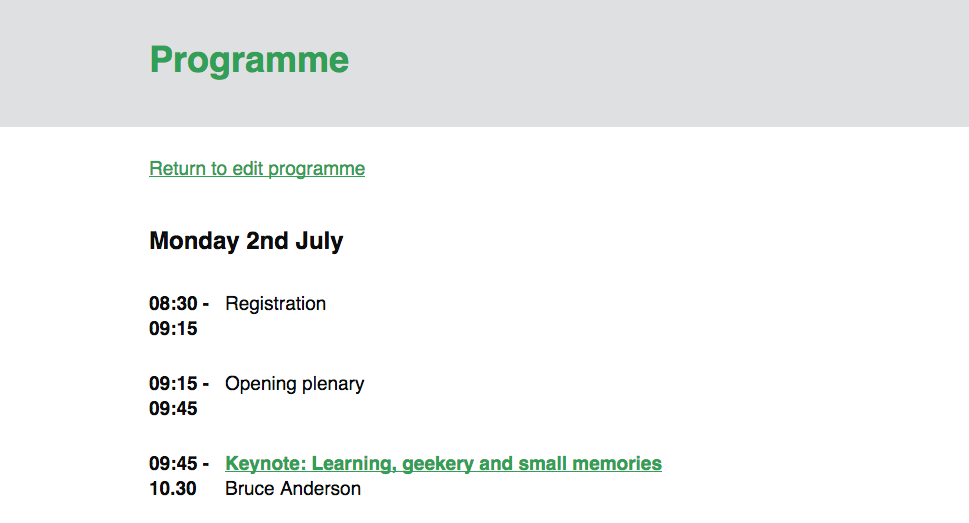

I also added the ability to preview the page exactly as it would look on the site.

And the publish button now actually publishes to the live site, by saving it in the correct place on the filesystem.

I’m not very happy with the separation of the generation of the static pages from the generation of the programme, especially as there is a chance they could be briefly out of synch (e.g. if you add a new menu item and republish the site but do not republish the programme). In practice, this will rarely happen as once the programme is published it tends to be frequently republished as things change, e.g. session leaders update details of their sessions. However, I see this as an area to be improved in future.

The preview and publish code both reused the code from the previous editing of the programme to generate the full info for the session, including a link to the session page and the user pages.

In addition, I made it so that publishing the programme also publishes those session and user pages rather than requiring the extra step of the publishallsessions.php script..

(This meant, before my changes, if a user updated their bio and asked you to publish it you would have to run publishallsessions.php in the browser, then navigate to the edit programme page in the site and hit the publish (to staging only) button, and then run publish.php in the browser. Now, you just navigate to the programme and hit the publish button.)

Tidying up after the programme

Finally, I deleted all the Xinha code. This was INCREDIBLY SATISFYING.

Tidying up after the CMS

But that was NOTHING compared to the joy of getting rid of the CMS. Not just the code – that was great – but also tidying the database.

CMSMadeSimple stores everything in the database, so once I’d removed it I could remove 54 tables. Added to the removal of the MediaWiki tables, in a few months I had gone from a database with 113 tables to one with 10. This is so much better.

Also, because the publish.php script copied everything from staging to live, it meant that there were several unused files that got copied over year after year. For example (check out the URL) https://spaconference.org/spa2010/uploads/images/spa2009/headersnaps/1.jpg. And here it is again in 2017: https://spaconference.org/spa2017/uploads/images/spa2009/headersnaps/1.jpg… and every year in between. It’s nice to tidy those things up.

Making it easier to develop locally

Removing the CMS also made it much easier to set up a local development environment. When I took over running the website in 2014, I did what I always do: set up a Vagrant box, managed by Puppet, so I have to do as little manual set up as possible.

Part of our setup of the CMS involved some modifications to the staging site, so I set up Puppet to copy over those modifications. These were things like the .htaccess BasicAuth. Removing the CMS meant I could remove a whole Puppet module, and also some manual instructions for setting up the site locally.

It also meant that developing locally didn’t require setting up a local version of the CMS.

What did the new chairs think?

I rushed to get this ready so that this year’s programme chairs could set up the programme for this year. They did this, using the site, and didn’t ask me any questions about it so I assumed it was straightforward enough to use.

At the conference, I managed to grab them to get their feedback, and they hadn’t felt quite as positive about it as I’d hoped. Initial response was “completely incomprehensible interface”.

However, they managed to use it rather than handwriting HTML, unlike any other chair since 2014, so I still call it a win.

We came up with some clear ideas of how to improve the interface to make it more useful and easier to use. However, one thing worth mentioning is that a lot of the programme chairs’ concerns were that it didn’t allow them to add all the information involved in generating the programme, like the speakers’ availability, their AV requirements, etc. That is by design; the aim of this form is to give chairs an easy way to generate the programme in the style of the rest of the site. The complexity of putting the programme together needs to be done elsewhere because we can’t assume chairs will do it in the same way. Some might use Trello, some spreadsheets, some index cards, etc.

However, I’m definitely going to make some improvements to make it more user-friendly to do the job it’s meant to do. Now it is in my control, rather than using an external tool, I can continue to iterate it to make it better.

Was it worth it?

If this had been part of my job, it would have been very hard to justify doing this work, especially as it took so long. The right solution would probably have been to buy a tool that doesn’t reflect our process, and change our process.

But this is a side project for me, and I enjoy tinkering and improving it, and in doing so it allows us to support our community-led and anonymous submission process.

And it is really satisfying to be able to do things that people like, and get that feedback. One of the programme chairs said the CMS made her feel stressed because she didn’t know what needed changing, but with the new Jekyll site, she could see what everything was and it felt “calming”. That is high praise indeed. When it’s all code, you can grep, but with the CMS you might not be able to find what you are looking for.

And another huge advantage of making the static pages open and accessible to others is that when something on the site broke, in this case the build, it wasn’t just an email to me to do something; someone else could fix it.

Roll on open sourcing the rest of it!

If you’d like to be notified when I publish a new post, and possibly receive occasional announcements, sign up to my mailing list: